We’ve likely all read that practice makes perfect, or heard the benefits of practicing how you want to play. But there are methods to improve in almost any discipline that are less obvious than repeating the actions of the discipline, and writing is no exception. In this post I will share what I refer to as increasing your capacity to write.

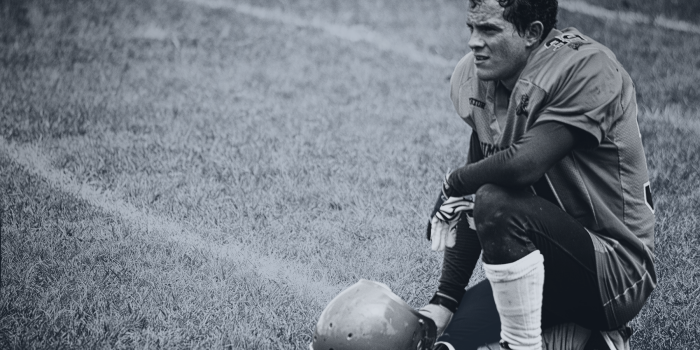

Although this concept applies in art, music, science, and relationships, the easiest example to grasp comes from sports. Obviously, a football quarterback improves his ability through performing the tasks he uses in a game: throwing footballs, running through plays, and scrimmaging against mock defenses.

But he also improves his capacity to play by lifting weights, running sprints, and drills to improve his reaction times in general.

IMPROVING THE ABILITY TO WRITE

The self-evident activities for improving our writing ability include journaling, writer’s prompts, and exploring other genres or forms.

Less apparent are methods of increasing our capacity for writing and our capacity as writers, wherein the focus is less about the writing per se. Some informal examples of these exercises that members shared at the WCCW meeting in March are eavesdropping/listening, hiking, meditating, reading, and studying other languages and cultures. They increase our working vocabulary. They flesh out characters. They increase the breadth and depth of our perception.

Somewhat ironically, teaching increases our understanding. When I was asked to speak at the WCCW meeting, I had a loose concept of sharing how I had forced myself to grow by writing a haiku per day using only what I could see out of a 4″ x 48″ prison window as my subject material.

In developing the class, I also recalled the growth I experienced trying to encapsulate pieces of classic literature into a single limerick. I read about a native elder who encouraged tribe members to sit and look at only a 3 foot by 3 foot piece of ground for a set period of time; over time that small area opened into a whole vast world of interesting things usually overlooked in the rush of life.

I looked for a way of explaining these processes as universally applicable truths. My attempt to add clarity without resorting to cheesy, dated graphics is the following:

LIMITED SOURCE + STRICT STRUCTURE = INCREASED CAPACITY

Applying the example processes from above, in prison I limited my source material to what I saw out my tiny window. I forced myself to take what I saw and write about it using the strict structure of the haiku*. I used the limited source of a piece of classical literature and wrote about it confined by the strict structure of the limerick poem. These exercises required me to find words and synonyms that matched my syllable, rhyme, and subtle meaning needs.

* Traditional Japanese haiku are poems consisting of a line of 5 syllables, a line of 7 syllables, and a line of 5 syllables. Due to the particular framework of the Japanese language (wherein words are constructed of syllables) as compared with English (wherein words are constructed of letters) duplicating the effect of a Japanese haiku for the writer and the reader works best in English with a line of 3 syllables, a line of 5, and a line of 3, or 4-5-4. For the purposes of exercising your linguistic mind, the particular set of rules is less important than the fact that you are using rules.

Here are some examples to flesh out what I’m saying about increasing your capacity to write:

Warm spring sun

Leaves a window shape

On the cool floor

Angled sunbeams

Burning gilt-edged holes

Through deep clouds

Swarming pigeons

Befriend the lonely

Man with breadcrumbs

![]()

The Father, Son, and God-Wind

From beginning of time till the end

Gave clarion call

That was open to all

To live life as a special God-friend

The Bible

Now that I’m writing this, which is a form of teaching and as such is apparently broadening my perception of this idea, an even simpler over-arching conceptualization comes to mind. What we’re really looking at is how all growth comes through some kind of conflict, adversity, or obstacle.

There is no growth by jelly donut. We grow muscle through resistance training: moving something that is not easy to move. This breaks our muscles and our body rebuilds them larger and stronger.

In cardio-vascular training, we achieve growth by taxing our heart and lungs. In an educational setting, we grow when we encounter things we didn’t know before and have to strive to learn and apply them.

On my farm I learn to repair things following those things breaking, I learn better ways to garden from the failures in my garden, and I learn better animal containment practices after the goats and chickens have mauled the flower beds.

Just as for the first couple of forms of growth above we go to great lengths to facilitate or even create forms of conflict, adversity, or obstacles (e.g. gym equipment, training regimens, schools, homework problems), for our writing we can be quite intentional in our quest to grow by formulating exercises that are purposefully uncomfortable such as the ones I have recommended, or others.

In light of the revelation that there is no growth through jelly donut, we see that it is not the activity intrinsically that brings growth, but our dedication to stretching ourselves mentally.

If we choose to grow as writers by reading, we will likely not gain much by cruising through something as mind-numbingly inane as Janet Evonovich or Dean Koontz. This might be the reason that the haiku, cliff-ricks (Cliff Notes meet Limericks), and ground staring resonate and work so well. These forms of growth are likely not already in our wheelhouse. They are not comfortable. They require more deep looking, word searching, mind combing, and focus than regular, comfortable activities.

Forcing oneself to do the uncomfortable also includes the amount of exercise required for gain. We can’t expect a six-pack of rock-hard abs using a regimen of sit-ups twice a year. My prison haiku began as a daily exercise. More recently I chose to use haiku to find an answer to a difficult question posed by a friend: “what is the Spirit of God like?” You could substitute, “what is love?” or “what is life?” or any other vaguely nebulous question. I determined to write one haiku per day, but as my focus through my day was shifted to looking for things that harmonized in this vein, I wound up with 3-4 per day. Our days are busy and finding time for one more thing is hard, but mastering that discomfort is how we will gain from these exercises.

The fascinating thing about the increased capacity I’m speaking of, is that its effects are two-fold: not only does this practice stretch working vocabulary, word choice, and thought formation for our writing, it increases our perception on a broader scale.

When I gaze into a small patch of ground and begin to perceive each wandering ant, the breeze waving blades of grass, and a mislaid marble, this amplified attentiveness remains present when I move my eyes to another patch of ground, even a larger one.

In conclusion, I hope that regardless the method you choose, you can grow as a writer by growing as a person: grow in your ability to paint a verbal picture by developing the very picture you see, develop your word-craft by increasing the richness of your working vocabulary, and increase what your reader perceives from your writing by broadening and deepening your perception of the world around you.

- The Inner Game of Tennis - February 24, 2026

- Preemptive Creativity - November 28, 2025

- Defeating Writer’s Block - January 6, 2025